Completion accounts (or closing accounts) are essentially the financial position of the business on the day of closing, when ownership of the business is transferred from seller to buyer.

Completion accounts always have the balance sheet and, generally, the income statement positions for the period to closing.

For example, if the business’ financial year ends on December 31, and you acquire the business on March 31, the income statement portion of the completion accounts will be for the interim three-month period only.

If you are acquiring the assets of the business, then your New-Co (the new legal entity that has acquired the assets) will start trading on April 1, and the interim three months of accounts (and financial performance) will belong to the seller who has retained the old entity.

However, if you are buying the shares in the business, then the financial performance during the interim period is yours to keep.

But the most important part of completion accounts is the balance sheet since this can have a direct impact on the closing payment.

In a recent post, I wrote about net working capital (NWC) and why it’s critical in any deal. NWC is the difference between a company’s current assets like cash and accounts receivable (AR) inventory… and its current liabilities such as accounts payable (AP), notes payable and taxes due to the government.

NWC is very closely linked to the concept of completion accounts in respect to the balance sheet position you inherit, and it’s important to negotiate this number to be as high as possible.

Here’s an example…

Assume you studied the NWC of a company for a minimum of 12 months to account for the seasonal nature of most businesses.

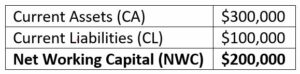

The NWC values were as follows…

So you negotiated the seller must leave the average NWC of $142,500 in the business on the day of closing.

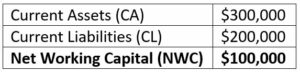

But let’s assume at closing, when the completion accounts are generated, these are the positions on the balance sheet…

(Remember, the net working capital equation: CA – CL = NWC.)

In this case, the seller has left MORE working capital ($200K) than originally agreed to ($142.5K), so this will require a ‘true-up.’ This means you will have to PAY the seller the $57K difference.

Depending on how it was written into the deal documents, you can pay it immediately, you can pay it after a period of time, or you can add it to the seller financing portion if one exists.

But what happens if the seller delivers LESS working capital than promised? If that’s the case, you would DEDUCT the difference from the closing payment, which is exactly why you need to have this information available at closing.

How? Simple…

Most small businesses operate on an established accounting platform such as Sage, Xero, Quick Books, etc. On the day of closing, ask for a balance sheet statement from the close of business the previous day.

This will give you the current assets and current liabilities levels.

Remember, assets are stuff the company OWNS, like cash, AR, inventory, etc.

Liabilities are stuff the company OWES, like AP, notes payable, taxes, etc.

Now let’s assume at closing you run the balance sheet and the numbers are:

Wait, that’s lower than agreed…

So now you need to make the adjustment. The seller has left you with a $42,500 shortfall.

Now, depending on the deal documents, there may be a ‘buffer’. A buffer is often a $5,000 or $10,000 allowance (in either direction) to give the working capital position a small degree of flexibility. Let’s assume this was $10,000.

Now the shortfall is $32,500.

Under the terms of your contract, you can DEDUCT the $32,500 from the closing payment.

So if your closing payment for the business was to be $250,000, you will now only pay the seller $217,500. The $32,500 of additional financing you’re left with goes back into the business to replenish the shortfall.

You are still $10,000 worse off (via the buffer), but this could easily have worked in your favor if the deal went the other way.

So that’s why the completion accounts mechanism is critical for closing deals, regardless of which way it goes.

If you have a shortfall, it’s best to know at closing so you can adjust the closing payment. If it’s a surplus, negotiate to paying it later if you can.

Until next time, bye for now.