We’re seeing a lot of questions right now on the Dealmaker Wealth Society Facebook page about add-backs.

Specifically — what are they? And why are they important in doing deals?

Those are great questions. And the answers are pretty simple…

An add-back is an adjustment to the operating profit (EBITDA) for a business you want to buy.

EBITDA is a commonly used statement of profit. It’s the measure we use to value all leveraged buyout (LBO) deals. It means…

- Earnings (retained profit of the business, the lowest line on an income statement)

- Before

- Interest (financial interest paid by the business on any debt or financing currently being deployed)

- Taxes (what you pay the government)

- Depreciation (the write-down, or reduction in book value, of fixed assets — vehicles, equipment, computers, furniture, etc.) and…

- Amortization (the write-down of intangible assets, or assets you cannot see — goodwill, patents, trademarks, other intellectual property, etc.).

When a broker makes adjustments to the EBITDA, these are called add-backs.

The add-backs represent what the profit will be once the owner has transferred the business to you. It’s a retrospective statement of profit with YOU as the owner and not the SELLER.

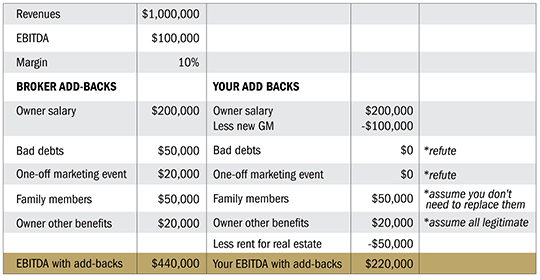

Let’s look at a few examples of add-backs…

Owner salary/compensation

If the owner is taking $200,000 per year in income yet the market rate for a general manager (GM) to operate the business for you is only $100,000, there will be a $100,000 legitimate add-back.

Here’s how it works: The seller leaves and now the profit is increased by $200,000. However, when you employ your GM (or promote from within), that will cost you the $100,000 annual salary. So the net add-back is $100,000.

The owner may also have benefits running through the business that can be added back to EBITDA — a car, pension contributions, insurance costs (though you may have your own insurance to put through the business so this may not be a legitimate add-back).

And the owner may put other costs through the business, including paying a spouse or other family member a salary, family vacations, etc. These are legitimate add-backs — but a word of warning…

This is essentially tax fraud by the seller. Your contingent-fee CPA will uncover this through financial due diligence.

Other add-backs you may see that you must refuse include…

Marketing expenses

A seller (or broker) may want to add back one-off marketing expenses, like an event. I refuse these.

That marketing event will have probably driven revenues and earnings, and since you are buying the business at a multiple of earnings, the marketing event is NOT a legitimate add-back. So refuse this.

Nonpayment of customer invoices

All businesses have bad debts. It’s just the way of the business world. A seller (or broker) may want to add back bad debts. REFUSE THIS. It’s not a legitimate add-back.

Negative add-backs

One negative add-back — where you reduce profit — occurs when real estate is involved.

Let me explain…

Say you’re only buying the business and not the real estate it trades out of.

The seller is keeping the real estate, and as the new owner of the business you have to pay rent.

This is a negative add-back because the profit will be reduced by the new requirement for you to pay rent.

All right, let’s run through an example…

As you can see, negotiating the add-backs makes a MASSIVE difference to the value of the business.

- The original profit is $100,000…

- And the seller (and/or broker) is restating that to $440,000 — an increase of 4.4 times!

- But the real EBITDA with add-backs is $220,000 — half of what the seller or broker originally stated.

Inside my Dealmaker CEO program, I give you a template to help you calculate the EBITDA and add-backs in detail.

This expert training system could save you hundreds of thousands of dollars negotiating the right numbers.

Click on this link to register.

And keep your questions coming!

I will speak to you soon.

Until then, bye for now.

Carl Allen

Editor and co-founder, Dealmaker Wealth Society