Our private Facebook groups have been on FIRE lately…

Even if you haven’t bought one of our programs, you should request access to Dealmaker Insiders — it’s FREE to join, and has some very active members sharing their dealmaking questions and tips.

This particular installment in our WTF series was inspired by a question posted in that group.

SPV is an acronym for special purpose vehicle (sometimes also referred to as a special purpose entity or SPE.)

But what exactly does that mean?

An SPV is a legal entity used to isolate financial and legal risk — and it’s the legal entity we use for acquiring businesses.

When you are buying your very first business, you as an individual do not make the acquisition. .

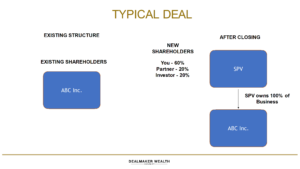

The SPV will own the acquired business while you individually (and any shareholders or partners) will all sit as shareholders in the SPV.

The SPV is also often called a holding company (holding co) or a top company (top co). They all mean exactly the same thing.

If a business you are targeting has a top co, it’s a clue that the business has changed hands before.

If your target business doesn’t have a top co, it’s likely still owned by the individual or individuals that founded it.

Let’s look at an example…

You find a business to buy… call it ABC Inc.

Assume you are not an expert in the industry but your friend Jim is. He agrees to co-own and co-run the business with you.

Neither of you are pledging cash into the deal, and Jim is happy with a 20% ownership stake for limited involvement… enough to get the deal done and set up the strategic plan post-closing.

There’s a GM in the business already who will operate it day to day, so neither you nor Jim have to.

But as part of your deal structure, you need an equity investment.

Assume the deal is $1 million in total consideration, structured as follows:

- $500,000 closing payment

- $300,000 seller financing over three years

- $200,000 earn out.

The $500,000 closing payment is a $100,000 equity investment from an angel investor named Brian, and $400,000 in debt financing.

Brian wants 20% of the deal for his $100,000 investment.

Now you, Jim and Brian are all shareholders of the business. You all hold your shares in the SPV, and the SPV owns the business 100% post-closing.

SPVs are also very useful for separating assets from a business to protect against financial or legal risk.

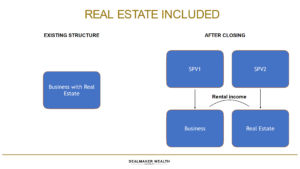

Say you buy a business that includes real estate. The smart move is to do the deal as two separate transactions.

First buy the trading business and drop that into one SPV (let’s call this SPV1). Then buy the real estate and drop that into another SPV (let’s call this SPV2).

SPV1 (the business) pays rent to SPV2 (the real estate business), which also has the loan that you probably used to finance the deal.

This way, if the business fails, the building remains under your ownership and you can either sell it or just find a new tenant. (You will most likely need to do one or the other since you will still have the real estate financing to pay off.)

Here’s another example…

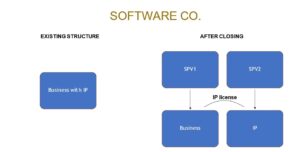

Imagine you buy a business in software and it has valuable intellectual property (IP).

It’s a great idea to carve the IP out into a separate SPV and then have the software business pay a license fee to use it.

This way, if the software business fails, the IP is protected and you can sell the IP or license it to another software company.

Finally let’s look at SPACs.

No, it’s not a term from Star Trek. It’s another, more complicated form of an SPV.

SPAC is the acronym for special purpose acquisition company. The difference between a SPAC and an SPV is that a SPAC is publicly traded.

It’s a hot trend on Wall Street right now. It’s essentially a vehicle to leverage public money to buy businesses in IPO-style fashion.

Yes, it’s expensive, takes a ton of time and is rather complex. However, it allows dealmakers can go after larger deal, since they can raise capital at higher valuations via the IPO model.

Why? Because publicly traded companies are more liquid (there’s a market to buy and sell shares quickly) versus private businesses where liquidity is limited.

So SPACS should only be used on big boy deals.

For your first deal (and first 10 to be honest), stick to the SPV format and keep your acquisitions structured in a legally and financially efficient way.

Until next time, bye for now.